THE JOURNEY BEGINS: The Olympia is loaded onto the zeppelin in Friedrichshafen.

Starting in 1934, Opel models came with hood ornaments in the shape of a stylized zeppelin. These early 20th century flying machines served as a symbol of progress, innovation, and globalization. Zeppelins, which looked like giant airborne cigars, were rigid airships with skeletons made of rings and girders. They could cover 16,000 kilometer stretches without having to stop for a landing – since airplanes of that era were only able to handle much shorter excursions, zeppelins were considered the future of air travel. For many, zeppelins represented a way of bringing continents together.

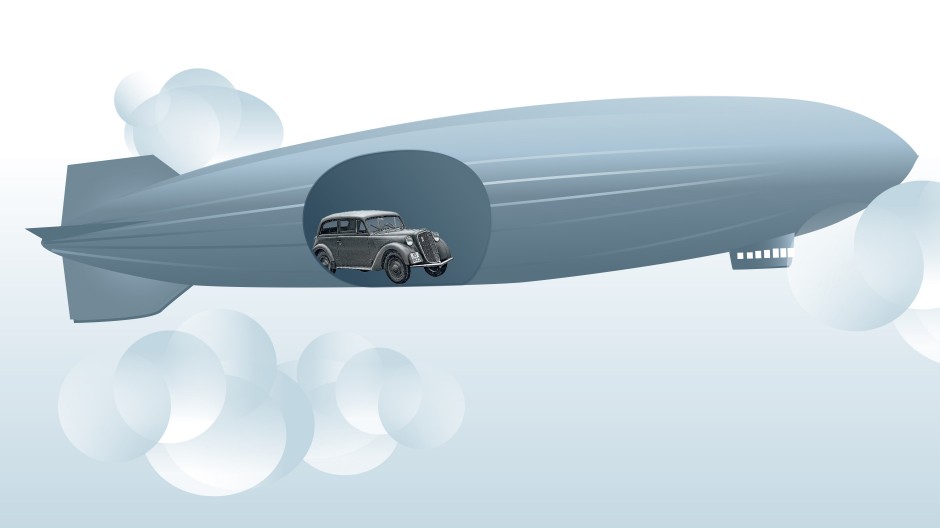

When it came to zeppelin production, Luftschiffbau Zeppelin GmbH ruled the skies. Down on the ground, Opel enjoyed a similarly exalted position in the automotive industry. Luftschiffbau zeppelins and Opel cars were both marvels of lightweight construction that made Germany proud, a commonality that inspired Opel Press Liaison Dr. Carl T. Wiskott to come up with an electrifying idea. Wiskott sought to publicize the introduction of Opel vehicles to the Brazilian market in 1936 – he wanted to create a media spectacle around the arrival of the first cars from Rüsselsheim, Germany in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Wiskott decided that an Opel Olympia, the first mass-produced vehicle with a self-supporting full steel chassis, should be flown to Sugarloaf Mountain inside of a zeppelin – stunning the world with a marriage of innovative German transportation technology.

Wiskott’s vision still seems daring today, and bordered on the outrageous back in 1936 – at that time, a car had never been transported as air cargo before. This bold vision become a reality: On 30 March 1936, the L.Z. 129 lifted off from Friedrichshafen, Germany. This massive, cigar-shaped airship, which was 245 meters long, 41 meters high, and weighed 220 metric tons, carried a roughly 800 kilo Opel Olympia in its belly. This particular model was the 500,000th Opel ever produced, and had rolled out of the Rüsselsheim factory just a few days before.

AN 800 KILO CAR IN A 220 TON AIRBORNE CIGAR

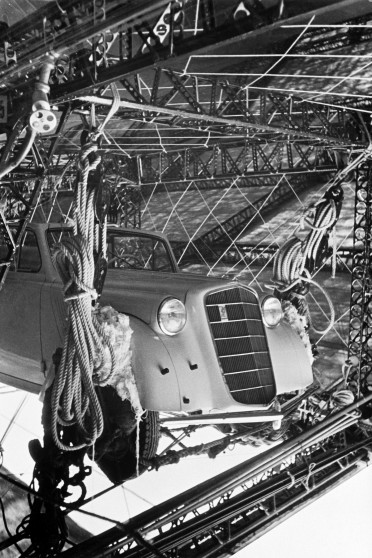

Opel reporters watched technicians load the car into the zeppelin, and described the affair in breathless detail: “The car garage, if one could call it that, is located midship on the starboard side, directly beneath the walkway. The aluminum frame supporting the walkway has a delicate look, but it is strong enough to securely support the weight of an average vehicle. Four pulleys are suspended from above. On the floor of the hall, the Olympia’s wheels are slid onto knotted ropes of Manila hemp, and cushions are laid onto the disc wheels to prevent the rope around the chassis from breaking. A dozen technicians labor away in unison, and now the car is floating up into the body of the airship.”

This model was the 500,000th Opel ever made.

“Slid onto knotted ropes of Manila hemp”: The Olympia was tied up in the cargo hold.

The Opel car ended the first leg of its journey on the zeppelin’s aluminum frame.

–––

It took the Hindenburg three days to cover the 11,000 kilometer route.

–––

For the logisticians overseeing the project, this flight was a pilot test, not just a PR stunt; as the Opel report stated, “This won’t be the last time a car is loaded onto an airship – cars will become regular cargo on the Hindenburg.” The report expressed faith in the zeppelin’s future potential: “It is perfectly conceivable that well-to-do airship travelers will adopt the custom of bringing their cars along on board.”

CRUISING OVER THE ATLANTIC AT 131 KM/H

The hull of the aircraft contained 25 cabins and lounges for a total of 50 passengers. The zeppelin was powered by four diesel engines with a combined horsepower of 4,200 hp, and the average cruising speed was 131 km/h. It took the Hindenburg three days to cover the 11,000 kilometer route.

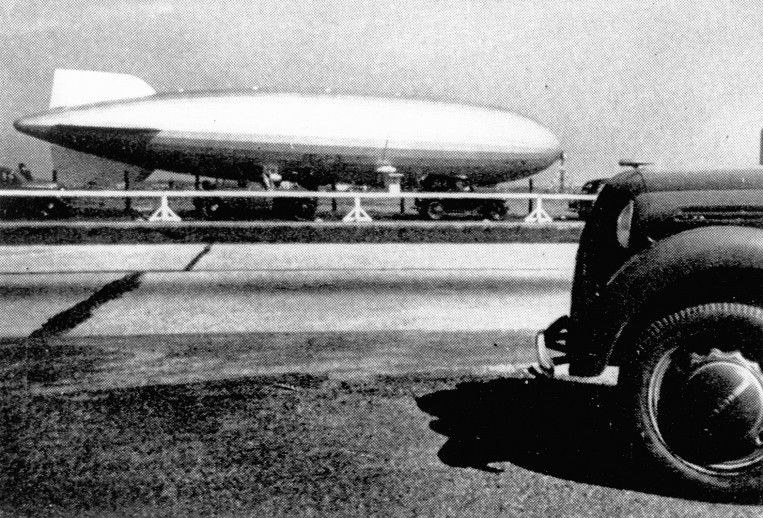

ARRIVAL IN SANTA CRUZ: The Hindenburg reached its destination after a non-stop journey of 11,000 kilometers.

The zeppelin received a warm welcome from the Brazilian Minister of Transport, the Marquis de Reis, and many other representatives of the Brazilian government upon its arrival at the international airship harbor in Santa Cruz, Brazil. As the hatch to the hold opened and the car inside was revealed, a frisson of excitement spread like wildfire through the crowd: “There’s a car in the zeppelin!” The Minister and his family were then driven in the self-same car to Rio. Opel reporters described the thrilling scene: “Deafening honking and screeching police sirens mixed with storms of applause from the masses of onlookers crowding the streets.” The ride ended at the Opel general agency in Avenida Rio Branco, where “the Minister of Transport put the car up for auction in a festively decorated room.”

LOSING TRACK OF THE MODEL

After this auction, Opel lost track of the model that crossed the sea. Nevertheless, it sparked a highly visible trend: The Olympia became extremely popular on and around Sugarloaf Mountain in the following years. This popularity has endured – one can still spot the odd Olympia on the streets of Rio today.

The Hindenburg traveled back and forth between Friedrichshafen and Rio de Janeiro a total of 19 times in 1936. This storied airship met a tragic demise on 6 May 1937, when, upon landing at an airport in Lakehurst, New Jersey, the hydrogen inside of its tank caught fire. 36 people lost their lives in the resulting explosion, which brought an end to the era of airship transport. In 1950, Opel removed the zeppelin from its logo.